Tabbouleh with Farro

introduction

Traditionally made with cracked bulgur rather than farro, tabbouleh isn’t about grain. It isn’t about the crisp, tailored dice of cucumbers and tomatoes or the Mediterranean elixir of lemon and olive oil. Tabbouleh isn’t about the bright stab of mint or scallion. Tabbouleh is fundamentally about parsley. Not parsley as a prop, not parsley as an accent, but parsley as a star—the main ingredient in a chilled, quenching height-of-the-season salad.

Back in Jefferson’s day, of course, before farming had mowed parsley down to two picks—curly and flat—parsley claimed abundant variation in flavor and leaf configuration, and was treated like a salad green or an herb, not like a corsage. This was certainly the case in Lebanon, where tabbouleh grew up.

Today, for all practical purposes, choices don’t really even come down to curly and flat anymore—if you’re using parsley as an herb, choose flat-leaf. Curly parsley is springy and cute, easy to chop and slow to bruise, but it doesn’t have a lick of flavor. Save it for the prom.

Having downplayed the role of grain in tabbouleh, we’ll now go on record as noting that tabbouleh, in our opinion, is appreciably better made with farro than with bulgur. Grain is resident in tabbouleh for the purpose of drinking up outlying flavors. Farro performs that task roundly—with bounce and verve. Eating tabbouleh made with bulgur is like driving a sedan down a long, flat road; eating tabbouleh made with farro is like driving a sports car over a series of short, curvy hills—it’s just a lot more fun.

Cooking Remarks

This dish requires next to no cooking, but if you dump the vegetables in the food processor or take a hatchet to them, you’ll wind up with gazpacho. A bit of hand artistry divests the tomatoes and cucumbers of their guts and seeds and transforms them into trim, meaty fillets that can be cut into a tiny dice known as brunoise. Expect to have some leftover trimmings, though.

Occasionally, tabbouleh recipes call for sumac, a culinary and medicinal herb, dried and used in a number of Middle Eastern preparations. It has a bright, astringent finish. Sumac is pleasing, but it doesn’t make or break the dish, in our opinion. Those who wish to pursue authenticity rigorously will encounter any number of arcane spices from the Fertile Crescent that have been associated with tabbouleh, but their search will likely be along the aisles of the Internet, not the grocery store. In the Middle East, tabbouleh is usually scooped onto spears of romaine lettuce and eaten out of hand.

Tabbouleh is best experienced as soon as it is made, when its colors are at their vibrant best and its flavors bright and green. On the second day, the tabbouleh will still taste wonderful, but it might have begun to weep quietly to itself, highlighting another advantage of using farro: it drinks up the delicious juices put out by the cucumbers, tomatoes, and herbs and keeps the salad from drooping noticeably.

equipment mise en place

For this recipe, you will need a paring knife, a citrus reamer, a vegetable peeler, a chef’s knife, a large mixing bowl, and a wooden spoon.

-

-

2medium cucumbers

-

3 or 4medium ripe tomatoes

-

1garlic clove, peeled

-

2bunches flat-leaf parsley, washed, dried, and stemmed

-

1small bunch mint, washed, dried, and stemmed

-

1scallion, trimmed

-

1

-

2tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil

-

2tablespoons juice from 1 large, juicy lemon

-

Fine sea salt and freshly ground black pepper

-

24small romaine lettuce leaves, washed and dried (optional)

-

-

Peel the cucumbers and trim the ends. Slice the cucumbers in half lengthwise and scrape away the seeds using a small spoon. Slice each half lengthwise into quarters, creating long strips. Each strip will have a thin, translucent band of flesh that held the seeds. Holding a sharp blade parallel to the counter, trim away that strip. Slice the fillets into thin strips between ⅛ inch and ¼ inch wide, and then cut crosswise into fine dice. You should have about 1 cup (fig. 1.1). Turn the diced cucumbers into a large mixing bowl.

-

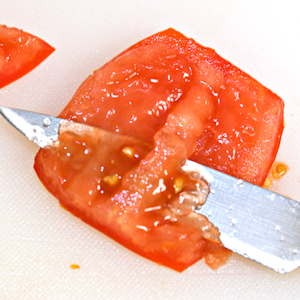

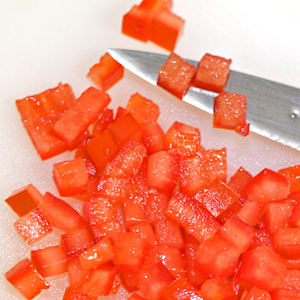

Stand each tomato on its bottom and remove the core with a sharp paring knife. Cut the tomatoes lengthwise into quarters. Place each quarter on its back and trim away the seeds and juicy flesh from the inside by slicing parallel to the counter (fig. 2.1). Discard the guts. Trim the edges of each quarter to make a neat, meaty rectangle, then slice off the remaining rib of flesh so the rectangle is flat (fig. 2.2). Cut each tomato fillet into thin strips between ⅛ inch and ¼ inch wide, and then cut crosswise into fine dice (fig. 2.3). You should have about 1 cup. Turn the tomatoes into the bowl with the cucumbers.

-

Cut the garlic clove in half lengthwise and smash it with the side of the chef’s knife, taking care not to obliterate it into several pieces. Stir the garlic into the tomatoes and cucumbers and set the bowl aside.

-

Grab a handful of parsley leaves and bunch it up against the side of the chef’s knife, then slice the leaves into fine julienne (fig. 4.1). Repeat until all the parsley is julienned. Julienne the mint in the same way. Slice the scallion into thin rings. Retrieve the crushed garlic from the bowl and discard it. Stir the herbs into the cucumber-tomato mixture. Add the farro, olive oil, lemon juice, 1 teaspoon salt, and ½ teaspoon pepper. Toss to combine and taste for seasoning. Serve straightaway with romaine leaves, if desired.

-

-

1.1

-

-

-

2.1

-

2.2

-

2.3

-

-

-

4.1

-